I was asked to give the keynote for the Atlantic Medieval and Early Modern Group conference held a few weeks ago in Halifax. I had a great time speaking to AMEMG researchers and other faculty and students from the Mount.

With such a diverse audience in mind, I started with broad concepts and gradually narrowed my focus to contemporary women’s rewritings of Beowulf, particularly the story of Grendel’s Mother. The following is a brief outline of some of my main points.

The first part of my title, “Dreaming the Middle Ages” comes from an essay by Umberto Eco in which he describes some of the different ways in which we have constructed our images (or “dreams”) of the Middle Ages. I talked about how the Middle Ages were named — invented, if you will — in the 16th and 17th centuries, mostly in negative terms, and how researchers in the 19th century constructed their particular brand of medievalism: white, imperialist, nationalist, masculine. I also talked about current efforts to change our labels, especially in the use of the term “Anglo-Saxon.”

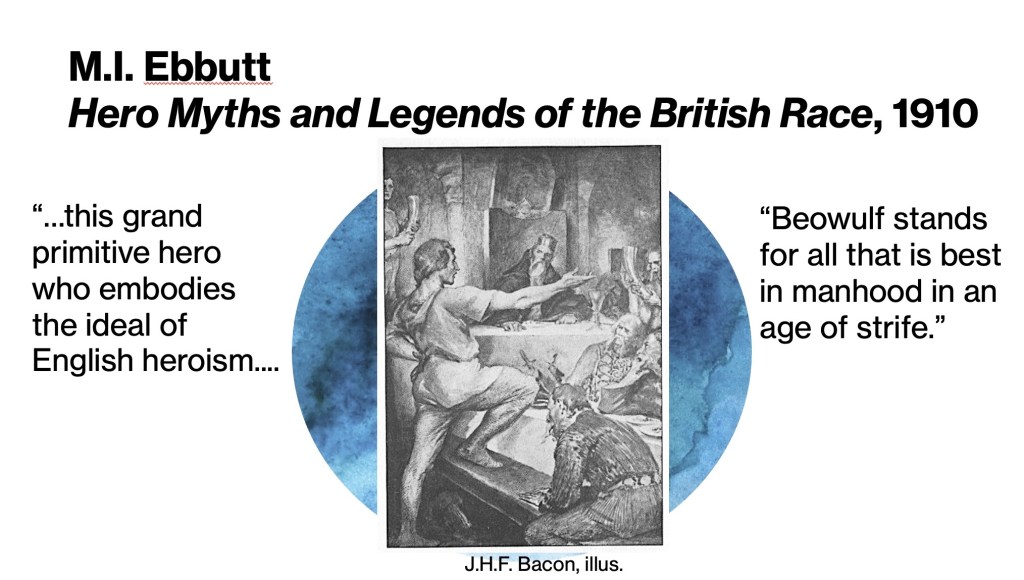

I then moved to considering the Old English poem Beowulf, and various statements about what the poem represented, from Danish researchers and translators who saw it as a Danish tale, to later Victorian and early 20th-century writers claiming it as the national epic for England. Moving into the 20th and 21st centuries, I looked at Tolkien’s statement in 1936 that Beowulf appeals profoundly to those “native to that [English] tongue and land” and Seamus Heaney’s idea that the poem should sound as if spoken by his Irish male relatives, whom he called “big-voiced scullions.”

All of these examples led to my main question, to whom does Beowulf belong? Who is Beowulf for?

After outlining Tolkien’s view of a bipartite structure in Beowulf covering youth and old age, I pointed out, as other critics have done, how the middle third of the poem includes women’s stories in what might be seen as a tripartite structure centering on Grendel’s Mother. I cited two examples of scholarly re-visions of Grendel’s Mother, one by Wendy Hennequin on monsterizing translations of Grendel’s Mother and another by Allison Vowell on how looking at Germanic analogues could help our understanding of Grendel’s Mother, who should be central to thematic links in the narrative.

Vowell summarized the problem in this way:

The women of Beowulf … have suffered from over a century of scholarship that does not always know what to do with difficult women.

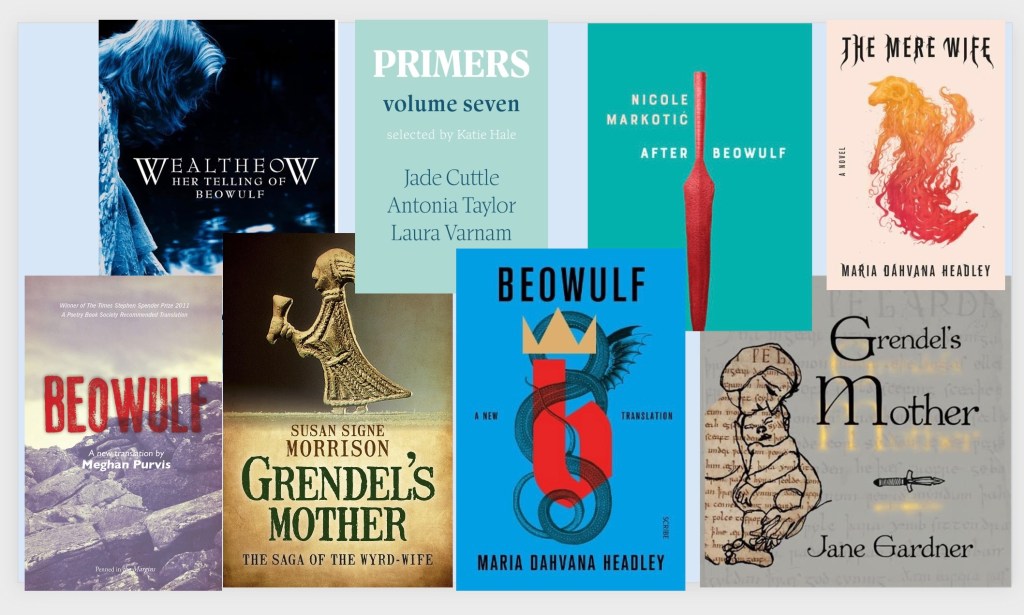

The final part of my talk looked at contemporary women’s rewritings of Grendel’s Mother’s story in poetry and prose.

As I said in my talk, each one of these texts could do with an in-depth analysis, but I only had time to point out a few common features in these writers who are claiming a space in the Beowulf tradition for different voices and points of view.

One of these common features was the challenge to the traditional narrator of the poem who presents a one-sided view of events favouring male warriors and leaders, obscuring the violence, especially against women and slaves, that upholds their power.

As Jane Gardner succinctly puts it in her poetic retelling:

The singer stinks of lies.

Laura Varnam’s poem “Grendel’s Mother addresses the Author” opens with these lines:

For all your bluster, warrior-poet,

Your puffed-up preening,

Your sword-swagger and shield-shuffling,

You still won’t look at me.

Susan Signe Morrison’s novel, Grendel’s Mother: The Saga of the Wyrd-Wife, expresses the difference between “official” versions and women’s knowledge:

The scop’s song still is sung. He sings of the hero’s exploits, the warrior’s wandering, the attacker’s act. The killer is sung as an avenger, the pirate’s a tribute-seeker, the rapist a good king. Only the peaceweaver is sung of with praise, her cup a tapestry doomed to unravel, her words of welcome weak…. The hero’s triumph overshadows the woman’s truth.”

I hope this gives you an idea of my topic. I don’t have the space here to include all of the other points I covered in 45 minutes, so I will just end here with the comments I made to conclude my talk:

Will the texts I’ve talked about today, only a tiny corner of the women’s rewriting market, challenge and forge a new understanding of Beowulf? And of course, it may not have escaped your notice that all of the rewriters in fiction and poetry I’ve talked about are white women – the result, I believe, of the persistent idea and reality that study of the “Anglo-Saxon” period has not been welcoming to people of colour. Still, I think there are signs that we are in the process of forging a different dream of the early medieval period through the work of both scholars and popular writers….

However we engage in this process of re-vision, I think that it is of paramount importance to keep asking and exploring, who is Beowulf for? To whom does it belong?

Selected bibliography

Crownover, Ashley. Wealtheow: Her Telling of Beowulf. Iroquois Press, 2008.

Gardner, Jane. Grendel’s Mother. Lasavia Publishing, 2022.

Headley, Maria Dahvana. The Mere Wife: a novel. Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux, 2018.

——–. Beowulf: a new translation. Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux, 2020.

Hennequin, Wendy. “We’ve Created a Monster: The Strange Case of Grendel’s Mother.” English Studies, vol. 89, no. 5, 2008, pp. 503–523. doi.org/10.1080/00138380802252966.

Markotić, Nicole. After Beowulf. Coach House Books, 2022.

Morrison, Susan Signe. Grendel’s Mother: The Saga of the Wyrd-Wife. Top Hat Books, 2015.

Purvis, Meghan. Beowulf: A new translation. Penned in the Margins publishers, 2013.

Varnam, Laura. In Primers volume 7, selected by Katie Hale. Nine Arches Press, 2024.

Vowell, Allison. “Grendel’s Mother and the Women of the Völsung-Nibelung Tradition.” Neophilologus, vol. 107, 2023, pp. 239–255 (2023). doi.org/10.1007/s11061-022-09738-5.